Grand SeikO timepieces offer futurism rooted in tradition

In 1923, the Great Kanto earthquake obliterated vast swaths of Tokyo. The tragedy included casualties of over 100,000 people with many businesses burnt to the ground. Among them was the watch repair workshop of Kintaro Hattori, founder of the Seiko Corporation. In the aftermath, Hattori took out an advertisement in the newspaper, to apologize for being unable to identify those who had sent their pocket watches in for repair. With records and the timepieces all reduced to mostly ash, his offered a free replacement pocket watch to anyone who came asking for one.

In the present day, both this advertisement and a bunch of melted pocket watches can be seen at the Seiko Museum in Sumida-ku, Tokyo. These artefacts stand as testimony of the indomitable spirit of Kintaro Hattori, something which his great-grandson, Shinji Hattori – the present Chairman and Group CEO of Seiko Holdings Corporation – continues to hold as the guiding light of the company. “Our desire is to continue his vision, of always being one step ahead of the rest of the competition.”

The historical perspective serves as a potent reflection of Seiko’s tenacity and conviction. Its success was initially achieved at great cost, with Kintaro Hattori choosing to pay on fixed dates, earning his suppliers’ trust. And despite being a loss-making outfit for 15 years after founding the Seikosha (Seiko meaning precision and sha for house) factory in 1895, he soldiered on and introduced automated machinery in 1910, which finally helped the business turn a corner.

Today, his legacy for a customer-first approach and his exhortation to always be ‘one step ahead’ is apparent across Seiko Holdings Corporation’s various business units; from watches, clocks, and timepiece components, to machine tools, mechatronic devices, semiconductors and eyeglasses. At its Morioka Seiko Instruments manufacture, the shadow of the magnificent Mount Iwate looms over the forests and streams. Blessed with a cooling climate similar to Switzerland’s, the land is famed for its old tradition of metals takumi (craftsmanship). Inside this zero-emission certified facility, on uniquely made workbenches and ergonomically styled Aeron chairs, master watchmakers assemble the Grand Seiko mechanical timepieces.

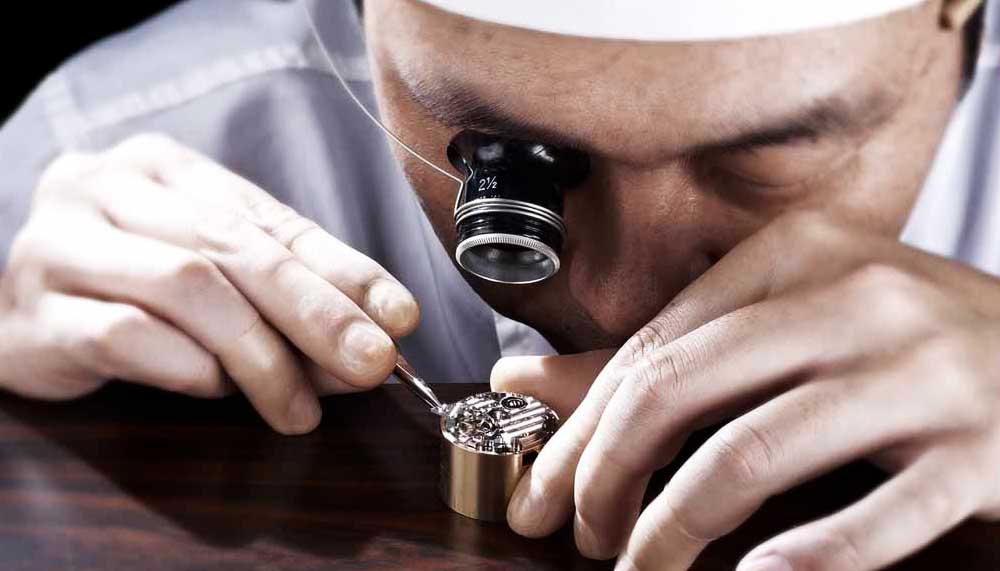

Since its debut in 1960, the Grand Seiko has served as this watch manufacturer’s top-of-the-line reference. At its watch studio, over 60 men and women are chosen to excel in various facets of mechanical watchmaking, with specialists in engineering, R&D, polishing, hairspring development and assembly. A certification system has been instituted to train ‘meisters’ in every competency related to the making of a Grand Seiko, with three tiers of achievement. The rigorous certification process means that a typical Gold Meister has at least 20 years of experience in their specialisation.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable achievements at this place is the fully vertical structure of its timepiece production. This process, which begins with R&D and design engineering, leads into the production of all movement parts – a marvel wrought by innovation and expertise. A special alloy known as Spron is constituent in its main spring and balance spring, providing balance and accuracy, plus a heightened resistance to magnetism and shocks.

Meanwhile, the Micro Electro Mechanical System (MEMS) – borrowed from Seiko’s semi-conductor arm – enables precision in watch components, through a machining process which is between two and five times greater than any other in the market. The culmination of all these qualities enable the realisation of its crown jewel, the Grand Seiko – an elevation of the pure essentials of timekeeping.

Approximately 700 kilometres south of Morioka, in the Nagano prefecture, one finds the Seiko Epson Corporation – home to the Spring Drive. It took almost two decades in the quest for the Spring Drive; which finally came to being in 1999. Despite its mechanical nature, the Spring Drive provides an accuracy on the same level as quartz (+/- 1 second per day) by virtue of a tri-synchro regulator. Power from the wound mainspring activates the integrated circuit which, in turn, applies an electromagnetic brake on the rotor speed. The result of this fusion of electro-mechanical physics translates into an aesthetically beautiful gliding motion of the seconds hand, with accurate timekeeping functions and efficient energy management.

The deep innovation in its Spring Drive movement is the continual elevation of Seiko’s mastery in horology. In the ‘60s, Seiko’s entry into the Geneva Observatory chronometer competitions saw it scoring more points than any other watchmaker. It also wrested the Petite Aiguille prize at the 2014 Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Geneve for the limited edition Grand Seiko SBGJ005 Hi-beat 36000.

At this plant, one meets engineer Masatoshi Moteki in the Micro Artist Studio. Operating in clean, modern surroundings, Moteki and his team are the bridge between tradition and the future of watchmaking. Their continual exposure to the larger world of watchmaking, through contemporary luminaries such as Philippe Dufour, helps them produce cutting-edge timepiece movements. But what is equally spectacular is their reliance to classical watchmaking codes – through textbooks like The Theory of Horology by The Swiss Federation of Technical Colleges which they used as the foundation of the Spring Drive Sonnerie, badged under Seiko’s Credor range of timepieces.

Seiko’s pioneering leadership in quartz technology – the company had introduced the world’s first quartz timepiece in 1969 – is also found in the Grand Seiko. The high-accuracy quartz, produced by Seiko themselves, is precise to +/- 10 seconds per year. Its 9F quartz calibre forms the heart of its top-of-the-line quartz timepiece, where the values of precision include an instant calendar change mechanism (responsive to 2000th of a second) and a non-twitching seconds hand, courtesy of a backlash auto-adjust mechanism. Shock protection from thicker metal plates, independent axes structure on the hands and a ‘super-sealed cabin’ for the wheel train further augment the timepiece’s durability.

Back in the plush confines of Wako, Ginza, Shinji Hattori reflects on Seiko’s long journey, one which began over a century ago. “We are engaged in an industry where tradition plays a big role; our users buy our watches to wear over decades and generations,” he says. “Seiko watches are built to fulfil this expectation of longevity. Luckily, Seiko is close to my family and we have the luxury to afford thinking about the business in a span of decades and generations.” This longstanding ability in pursuing true innovation and refining its level of craftsmanship is what the present-day Hattori feels are its greatest qualities. But he also humbly conceded: “it is a great help that we can look back to when my great-grandfather founded his company in 1881, and to imagine how Kintaro Hattori would have faced the challenges today.”