Sinuous Sensation

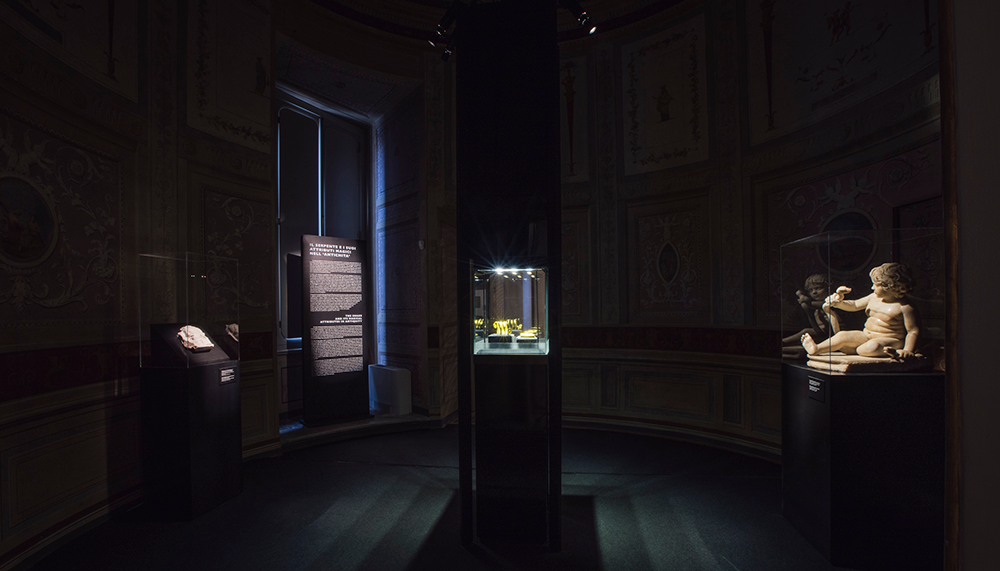

In the prolific world of luxury, one project often leads to the birth of another. For Bulgari, a coffee-table book forms the basis of an art exhibition. The brand’s SerpentiForm showcase ended its run in April in Rome’s Palazzo Braschi. “We started learning about snakes in art through the book that we just launched, Serpent in Art,” explains Lucia Boscaini, Bulgari’s brand heritage and corporate events senior director, who curated the exhibition. “Doing research for (the book), we realised that snakes are present in worldwide art. Creativity has for a long time been inspired by the snake. That was something that excited us, and we kept doing research. Finally we decided to have an exhibition featuring the snake as a creative element.”

Snakes are very much a part of the Bulgari identity, and have been so since the first coiled Serpenti bracelet-watches were unveiled in the late 1940s. Some of those early designs, on loan from private collectors, were displayed in the exhibition, alongside contemporary incarnations of the serpent, such as a new necklace in 18-carat pink gold, white diamonds, and snakewood, the first time that wood is being used in a high jewellery piece, Boscaini says.

The idea was to trace the aesthetic evolution of Bulgari’s serpents through the ages, from the early designs in gold hewn from the tubogas technique – a form of metal braiding used extensively by the house – to mid-century expressions ornamented with coloured gems, hard stones and enamels. “From the first (Serpenti) watch created at the end of the 1940s up till today, Bulgari’s creativity has evolved, but it still maintains the idea of a snake being worn around the wrist or the neck in a very subtle way,” says Boscaini.

The theme also came through in the paintings, sculptures, costumes, photographs and other objects on display. They included first-century CE gold arm jewellery from Pompeii, Elizabeth Taylor’s outfits worn in Cleopatra (1963); and sculptures of French artist Niki de Saint Phalle. “We wanted something close to the Bulgari aesthetic, which is playful and colourful, but still with gravitas and meaning,” says Boscaini.

Throughout history, snakes have been loved and loathed. It was a tempter in Christianity but a protector in Buddhism. In the Roman tradition, snakes were the favourite animal of Aesculapius, the god of medicine. Indigenous Australians worshipped the Rainbow Serpent as a creator, while Meso-Americans venerated the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl as god of the arts, crafts and knowledge. Boscaini, however, chose to steer clear of such historical or religious references, instead focusing on (positive) artistic representations of the snake – not an entirely bad decision, considering the sensitive nature of the subject.

Not all the 101 artworks in the exhibition are featured in the book. “We decided not to include all the things we found, because it would have been an encyclopaedia – huge!” quips Boscaini. But the tome – which illustrates how 32 international artists interpret the snake from the end of the 19th century until today, along with pictures and original sketches of Bulgari’s Serpentis – does have gravitas and meaning: thus serving as a fitting souvenir to one of the most iconic symbols of the world of Bulgari luxury.

Bulgari