Under the radar

Simon Majumdar, the British-American chef and judge of Cutthroat Kitchen and Iron Chef, once said in a Filipino magazine interview that he had “underestimated” Filipino cuisine. He called it “one of the few undiscovered culinary treasures left in the world, and if the people of the Philippines attacked the marketing of their food with the same gusto that they apply to eating it, it could be the next culinary sensation”. Another American TV personality, Andrew Scott Zimmern, host of Bizarre Foods, has said that given a few more years, Filipino cuisine would be “the next big thing”.

It looks like Majumdar and Zimmern are on to something. Not only is Pinoy street food fast gaining traction in the US, there has also been an emergence of chef/region-centred upscale Filipino restaurants in the Philippines itself. And for the first time, the Spanish gastronomy congress, Madrid Fusion, brought together the world’s most prestigious and innovative chefs in Manila in 2015. Many people see this event as the major push that would likely catapult Pinoy food onto the international stage.

At the heart of the movement is a bevy of chefs in Manila who are refining Filipino cuisine and bringing it to the next level. Fernando Aracama, for example, applies sophisticated cooking techniques to improve classic dishes such as Salpicao dela Casa. Tough and flavourful short ribs are cooked sous vide for 24 hours to tenderise them, then finished in roast garlic and black peppercorn gravy at his eponymous restaurant. Aracama, who is also vice president of the LTB Philippines Chefs Association, describes his cooking as traditional and modern. “I am beholden to the honesty of heritage and tradition but I am equally inspired by what I taste, see and feel when I travel and experience another country’s culture; and by talking, exchanging ideas and sharing techniques with other chefs,” says Aracama.

Others such as husband-and-wife duo Robert and Sunshine Pengson take inspiration from Filipino national heroes like Dr Jose Rizal to present creations that evoke emotions representing periods of his life. At their modern restaurant The Goose Station, they offer a manicured style of cuisine that narrates the story of the culture and history of the Philippines. Reviews have been mixed. “Some said it was genius, others literally stood up and left or laughed at me in the middle of my dining room, saying how silly it was,” shares Robert.

Most of the main protagonists driving this movement are Filipinos except for Jose Luis Gonzalez, or Chele as he is fondly called, a Spanish chef who cut his teeth with the likes of El Bulli, Arzak, El Celler de Can Roca and Mugaritz. Gonzalez melds modern techniques with indigenous ingredients and a tinge of playfulness to present Filipino food in a global way at Gallery Vask. He notes that Filipino food has been very basic so far and is mostly done to please Filipinos. “For Pinoy food to go to the next level, there has to be innovative, avant-garde restaurants that can elevate the country’s reputation and achieve a certain level of prestige so the rest of the world can see the potential of the food. On the other hand, from what is the norm and what is in the streets and inside (locals’) homes, we should refine, distill and make it more global so that a foreigner can eat and understand and start to talk about the food,” observes Gonzalez.

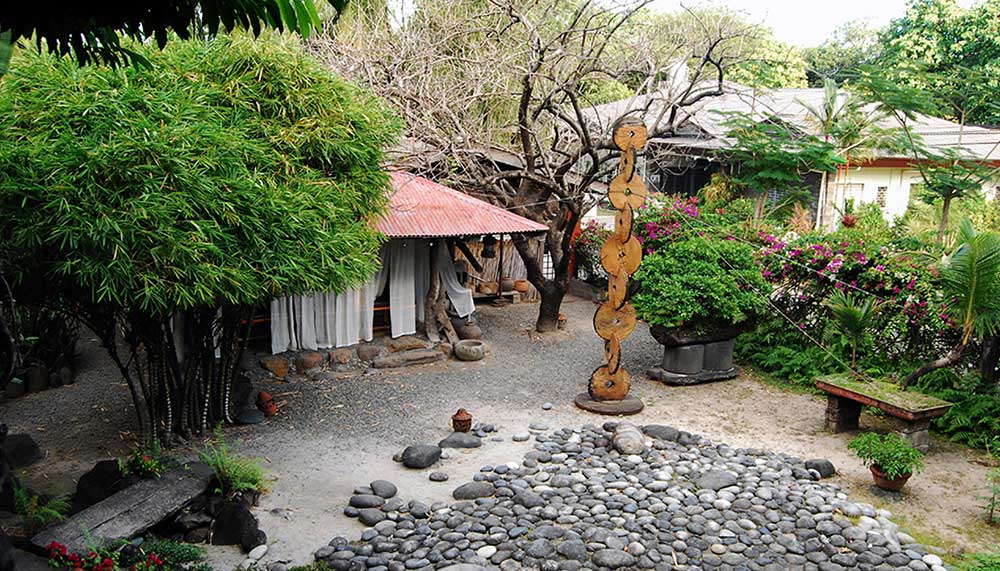

As chefs push for new frontiers in Filipino cuisine, there has also been a shifting of attitudes among Filipinos towards their own food. Claude Tayag of Bale Dutung – the traditional restaurant lauded by Anthony Bourdain for its Pampango food – says that the Filipino diner has come of age. “There has been a rediscovery and appreciation of our own cuisine. If we were our own worst critics before, we are our best ambassadors today,” he says.

Tayag recounts how he was invited to sell pork sisig in Makansutra’s World Street Food Congress 2015 in March, alongside Dedet de la Fuente of Pepita’s Lechon and Paul Qui, a Filipino-American from Texas, selling his fish kinilaw and chicken inasal tacos in a food truck. Tayag shares: “We probably had the longest queues among the 24 vendors coming from different parts of the world. At the farewell party, Makansutra’s founder KF Seetoh approached us saying: ‘Filipino cuisine is so good, man! Why are you hiding it from the world’?”

Filipino cuisine may not be as famous as its neighbouring counterparts, but all that is about to change.

What is Filipino Food?

Filipino cuisine can be defined by a few ingredients: coconut, vinegar and a whole lot of pork. Sourness, more than spiciness, is a defining characteristic of Filipino food. Calamansi is used in a myriad of dishes such as kinilaw ceviches, tamarind stirred into sinigang soups, and unripe green mangoes eaten with funky bagoong fish paste. You will also find vinegar derived from sugar cane and coconut palm in every Filipino kitchen. Used for marinating, braising and glazing, as well as a dip for entrees and snacks, vinegar is the backbone of adobo, a national dish that consists of braised meat, seafood or vegetables in vinegar, soya sauce, garlic and other flavourings. The bold combos of sweet (tamis), sour (asim) and salty (alat) don’t quite resemble anything else in South East Asia. Rice is a must at every meal but the Filipino’s real love affair is with pork. Porcine obsessions take the form of lechon, or suckling pig either deep-fried till crispy or roasted on a spit.

Field Trip

Vask Gallery

Combining cutting-edge modern Spanish molecular techniques with indigenous ingredients, some of which even the locals are not familiar with, Jose Luis Gonzalez presents Filipino food in a global way at Vask Gallery.

Choose from two tasting menus, Lakbay and Alamat, which translate to ‘journey’ and ‘legend’. A must-try is the Pan de Sal buns with smears of coconut butter. The buns are doled out in brown paper bags so they look like they came straight from a local bakery. Isaw resembles the ubiquitous barbecued skewers of intestines sold in the streets, but is actually deep-fried strands of sweet potato dough.

Gonzalez’s fascination with indigenous edible leaves is evident in his playful and innovative dishes. Buro, a dish of fermented rice risotto and maya maya (red snapper) wrapped in banana leaf and steamed with lemongrass broth, is topped with torn-up pieces of mustasa (mustard green) leaves.

Inspired by the Aeta tribe who live on Luzon, Gonzales created Binulo, a sour consomme similar to sinigang. He uses the alibangbang leaf from Pampanga instead of tamarind, and serves it with a frond of crispy leaf that hides tender cochinillo (suckling pig) and brown rice. The cherry on top is the after-dessert: Philippine candies called pastillas.

Aracama

While it is served in a modern setting, there are no crazy, head-scratching interpretations of Filipino food at Fernando Aracama’s eponymous restaurant. Instead, the chef-owner sticks to finely tuned local cuisine that’s elevated through contemporary techniques and elegant presentations.

Everyday dishes such as sisig showcase finely minced pig’s cheek, snout, ears and organs, while Chinese-style spring rolls such as Lumpiang Bangus pack smoked and shredded milkfish, sotanghon (glass) noodles and black ear mushrooms within the thinnest, bounciest crepe skin to make every bite a wonderful mishmash of textures.

The food is meant for sharing, but you probably want the Nilasing na Hipon – deep-fried baby shrimps marinated in gin and served with a vinegar dip or garlic aioli – all to yourself. Another winning dish is the Adobo sa Tuba. The charred flavour of the twice-cooked and crisped beef melds perfectly with the dark, savoury tuba (coconut sap) vinegar sauce. Crisp banana chips on the side are a pleasant tropical complement. Ensaladang Talong, a surprisingly smoky dish of grilled eggplant with edamame, is sure to elicit several appreciative gasps at your table. Aracama’s signature Choc Nut ice cream, inspired by the childhood chocolate peanut snack, is more familiar on the palate and makes the perfect sweetened conclusion to the meal.

The Goose Station

The name of the restaurant is a clever pun on the word ‘degustation’, but that’s not the only stroke of genius at the outfit fronted by husband-and- wife chef duo Robert and Sunshine Pengson. What started as a fine-dining establishment serving haute French-style cuisine in 2009 has transitioned into a more progressive local style when Robert took inspiration from the Philippines’ national hero Dr Jose Rizal to come up with dishes that evoke emotions representing periods of the icon’s life. Sadly, the restaurant shuttered its doors last year but remains a beacon of the progress that Filipino cuisine has made in recent times.

A dish of squab inasal with coconut curd, peanut puree, charred eggplant and cane vinegar is splattered with lashings of red beetroot puree to symbolise the tumultuous emotions in Rizal when he penned his provocative novel, Noli Me Tangere. Another appetiser of Visayan crab with fermented and fresh mangoes, coconut ice cream, extra virgin coconut oil, coconut sap vinaigrette, pink sorrel and cashews showcases pristine island ingredients before the colonial period. There are two tasting menus at The Goose Station. One is made up of the restaurant’s classics and the other is an experimental one that tells the story of the Philippines’ culture and history.