These Aviation Firms Want To Launch Their Own Space Stations By 2033

At the end of the decade, after over a quarter-century in orbit, the International Space Station (ISS) is planned to be decommissioned by NASA in order for the agency to focus on deep-space exploration, lunar flights, and journeys to Mars. That leaves low-Earth orbit, the layer 250 miles above the atmosphere, as the next frontier in commercial space enterprises. NASA seems all for it, supporting private developers via grants that promise to set off a gold rush of scientific research—and tourism.

“There will be at least one, maybe two, private space stations in the next 5 to 10 years,” says Tom Shelley, president of Space Adventures, which has been placing civilians on the ISS since 2001. But while he’s confident of the timeline, specifics remain vague. “Just exactly how big and their exact format is too early to tell,” he adds.

Cryptocurrency entrepreneur Jed McCaleb has founded Vast Space, a California start-up aiming to be first off the launchpad. In 2025, the outfit plans to send the Haven-1 module into orbit atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 as the inaugural segment of a new station. A SpaceX Dragon capsule mounted on another Falcon rocket (chartered by Vast) will then dock with Haven-1 so four tourist-astronauts can stay a few days.

Haven-1 will measure a modest 12 feet by 36 feet, but Vast also plans to build a “330-foot-long, multi-module, spinning artificial-gravity space station,” according to CEO Max Haot.

“Our focus is to crack the problem of artificial gravity and to make science fiction a reality.”

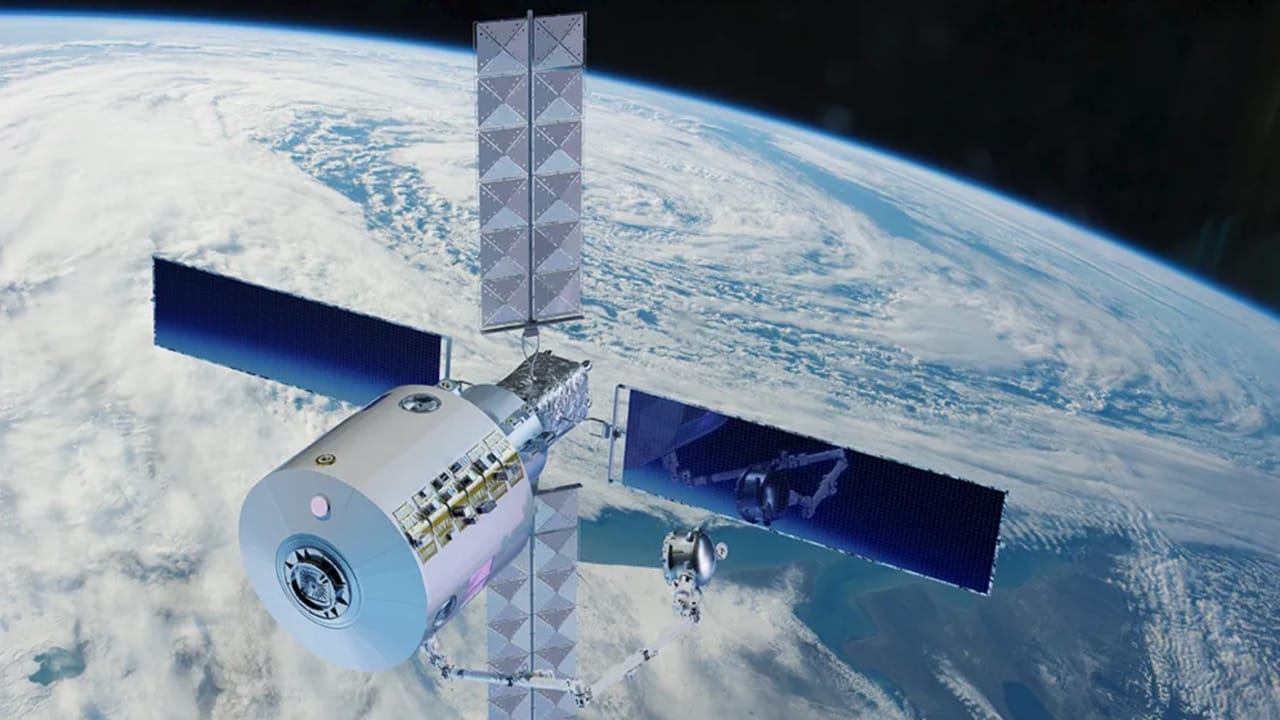

The competition includes other start-ups as well as established aerospace firms—Northrop Grumman could begin construction on a station as early as 2027, with its initial phase supporting four astronauts—and combinations of both. Colorado-based Voyager Space is joining forces with Airbus Defense to develop, build, and operate Starlab, a continuously crewed outpost slated to deploy from a single heavy-lift rocket before the ISS is decommissioned. Hilton Hotels is designing the astronaut suites.

Sierra Space, also based in Colorado, is partnering with Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin, Boeing, and the infrastructure specialists at Redwire to launch a “mixed-use business park” called Orbital Reef, which it hopes to establish by 2027. The plan is for it to house a hotel, restaurant, and labs for testing products in microgravity.

Meanwhile, Axiom Space is teaming with SpaceX, targeting 2026 to debut the early stages of its station, which will include Philippe Starck–designed crew accommodations and be available to everyone from governments to entrepreneurs exploring new research-and-development opportunities in the neighbourhood, as it were.

Tourism, it should be noted, will always be secondary to government-sponsored missions. “The space station is in orbit for 365 days per year, so operators need to find the best business case,” says Shelley, pointing out that “some of the developers couldn’t care less about private citizens, while others are super interested in what they can bring.”

Vast is in the latter camp, says Haot, though the term “space tourist” irks him. “These are private individuals who are real adventurers, more interested in furthering humanity’s understanding of space than going to a hotel in orbit.” The reality, though, will more likely be equal measures of both—and really, what’s wrong with wanting to enjoy a martini at a beautiful hotel bar in space?