Master Of Calendars

Patek Philippe has a close history with the perpetual calendar, with a patent for one filed in 1889. It had existed before then, but of the watchmaking houses as we know them, it is one of the earliest to have established itself in this regard. Patek Philippe was also the first watchmaker to put one in a wristwatch in 1925, when it added lugs to what was originally meant to be a ladies’ pendant watch. At this time, perpetual calendars were generally one-off commissions for individuals but, in 1941 Patek Philippe introduced its first serially produced perpetual calendars: reference 1526, and its sibling in the 1518 chronograph/perpetual calendar.

Already, the design codes that would come to define a Patek perpetual calendar — and indeed, a whole stylistic genre — were present at this early stage, particularly in the close-positioned twin apertures for day and month, and in the way the 6 o’clock date/moonphase subdial sits just on the minute track. At about 34-35mm in diameter, these two watches would run a little small by today’s standards (and speak to the maison’s ability to make a complicated movement in that size), but the case proportions and dial layout were exquisitely timeless. Patek calendars would go from strength to strength over the decades—for many references, it is not a question of whether or not it is a classic collectible, but rather how classic or how collectible.

But, as Patek would prove, there were still frontiers to explore. The perpetual calendar is the be-all and end-all of date-keeping; it is unfazed by the inconsistencies of the Gregorian calendar including 30- and 31-day months and the pesky problem of February and the leap years affecting it. A perpetual calendar needs no adjustment by its user, typically until the year 2100; needless to say, they are technical marvels that are extremely complex to manufacture. At the other end of the scale, there is the simple calendar: these are relatively trivial complications that essentially count from 1 to 31, and need the user to intervene at the end of every month that has fewer days — easy to produce, and still useful, but not particularly satisfying as watch appreciation and collecting go.

The missing link was unveiled in 1996, when Patek Philippe debuted the annual calendar complication on reference 5035. This only needs adjustment once a year, in February. It was designed from the ground up with user-friendliness and dependability in mind, and had a wheel-based mechanism instead of the rockers and levers found in a perpetual calendar. Ironically, this meant that Patek’s annual calendar movements have more components than its typical perpetual calendars. For many, this was a good compromise, offering an authentic calendar experience without the expense, rarity and sometimes finicky and fragile nature of the perpetual calendar. The annual calendar has since become a bit of a brand signature; not a grand complication, but a Patek complication nonetheless, and one the maison continues to invest in.

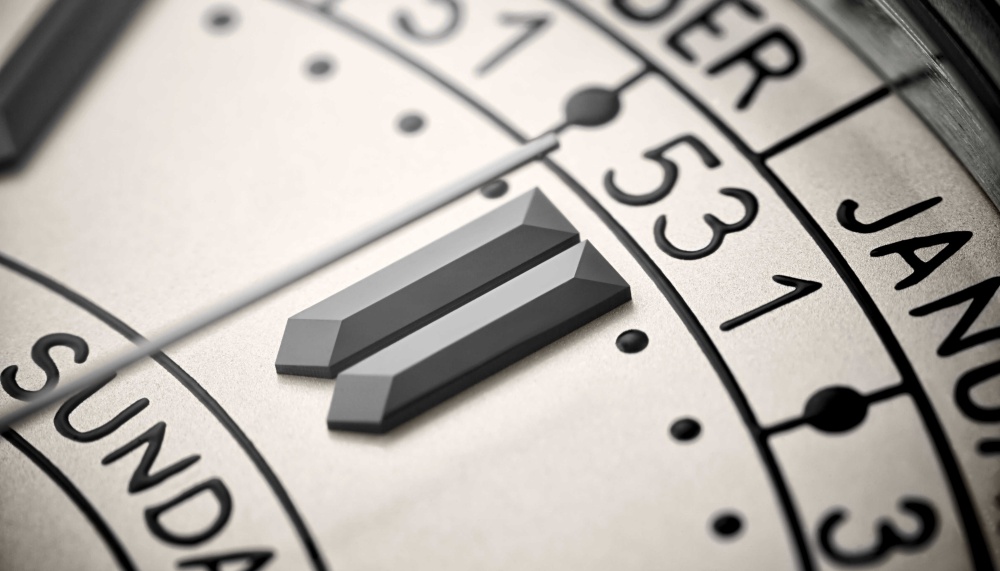

And there is still more fun to be had, if Patek’s new calendar release is anything to go by. The 5212A-001 Calatrava Weekly Calendar (SFr29,500) debuted at BaselWorld this year, and is relatively simple but unusual timepiece — one that Patek classes a ‘useful complication.’ In addition to day and date, this timepiece also has an indicator for week number in accordance with international standards; that is, 52 or 53 weeks in a year, depending. Additional quirks are found in the choice of layout, which involves a total of five centrally mounted hands, and the font choice on the opaline dial — it was based on the handwriting of one of the designers, lending the timepiece an almost jaunty and rustic sense. Perhaps most intriguingly, its case (40mm in diameter and 11mm thick) is stainless steel, one of the rare Calatravas in recent memory to be made of such — and in a mainline offering, no less. This, combined with the dial font, makes it a curiously casual watch, despite the classic case shape. This is definitely an oddball Patek Philippe, but the details are quite sublime — because it is a Patek Philippe.