Stephan Frauscher foresaw a wedding, but not anytime soon. His family’s eponymous shipyard, which launched its first wooden boat in 1927, had moved into electric boats by 1955. But they were slow, low-horse-power runabouts designed for restricted-access lakes in Frauscher’s native Austria and neighboring Germany. As the years went by, Frauscher built a reputation on gas-powered, performance motorboats, fast, seaworthy vessels ranging from 25 to nearly 45 feet.

As the electric-boat world has advanced in the last four years, with boats getting faster, sleeker, and more luxurious, Frauscher sensed a convergence was close. Top speeds routinely surpassed 25 mph, lengths grew beyond 25 feet, and hybrid options emerged. “We wanted to bring high-speed and electric together, but we were waiting until we could do it right,” Frauscher says.

Then one day in 2021, the phone rang. An iconic German automaker needed a partner to help them build a boat. Did he want in?

It was Porsche, a brand synonymous with performance and luxury, so Frauscher gave the only logical response: “I do.”

Last October, the Frauscher x Porsche eFantom launched in Geneva using the drive train from the Porsche Macan and showing off a top speed of nearly 50 mph, with the potential to break 60. At a 25-mph cruise speed, the 28-footer also had a respectable 30-mile range.

Performance is only part of the package, though. The helm recreates the interior look of a 911, including the steering wheel, instrument panel and seats. “I think it will make a great superyacht tender,” Frauscher says. “Wouldn’t it be nice to enter a fancy harbor in an electric boat with the Porsche logo on the side?”

It would, but turning heads in a battery-powered boat keeps getting easier. The eFantom is just one of a new breed of electric boats riding a technological wave that has changed the paradigm of what’s possible.

Improvements in hull design, drive trains, management systems, and even the addition of solar panels have led to electric-powered craft with high-level fit and finish and stylish design. A growing number of builders are also increasing the hull lengths and levels of luxury. Some are approaching 80 feet, a length that seemed impossible just two years ago.

“The difference is that we’re seeing more boats designed from the ground up to accommodate electric,” says Ed Sherman, a technical consultant for the American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC), who has been following the electrification of boats for a decade. It’s not just a simple case of retrofitting an existing hull with electric motors and heavy lithium-ion batteries. “It has to be engineered together to work effectively,” says Sherman. “All the better boatbuilders will tell you that.”

Car makers, too. Many of the new entries have connections with the auto industry, either through direct partnerships like the Frauscher-Porsche deal or via founders and key executives who’ve migrated from cars to boats. Other players include newcomers trying their luck as startups, or marine powerhouses such as the Ferretti Group’s Riva brand.

“The marine industry is so small that the investment to develop new technology often doesn’t make sense,” Frauscher says. “But the car business has so much volume they can afford it. We get the benefit of their R&D.”

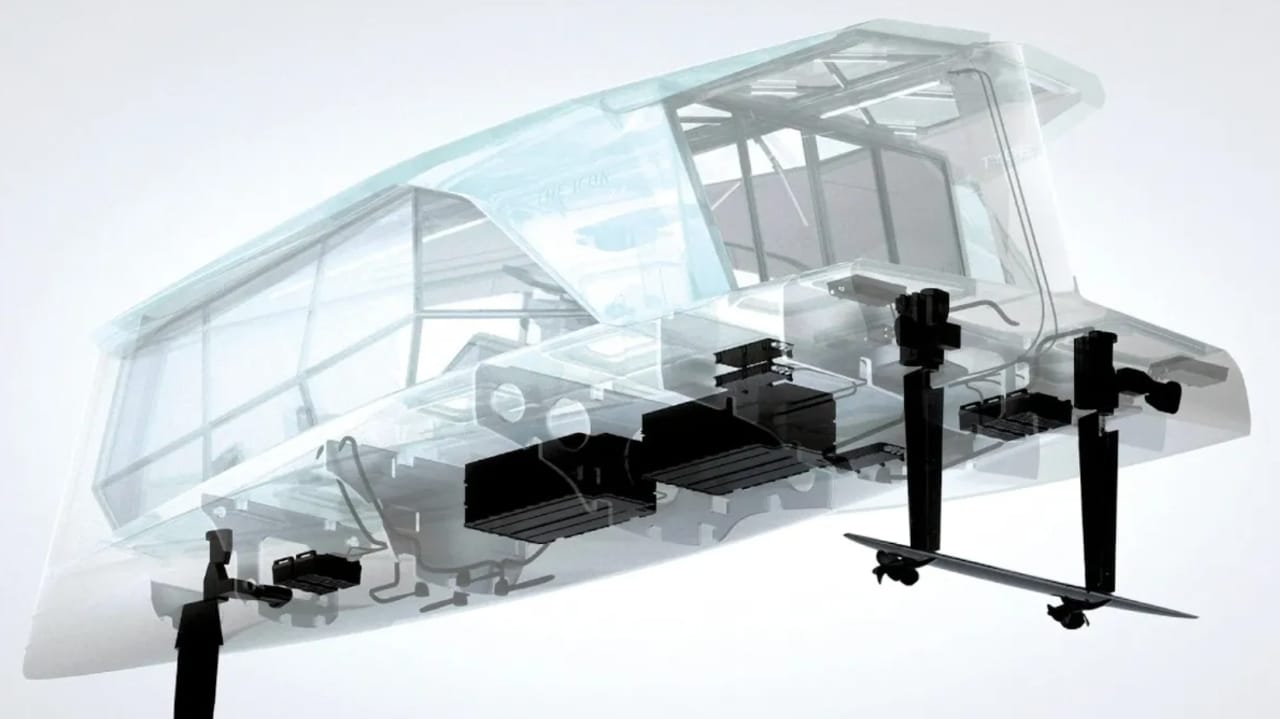

Tyde, based in Germany, has partnered with another luxe automaker. Its partnership with BMW has produced two unique and stylish foiling models, the 48-foot Open and the 43-foot Icon, that combine performance and pleasure.

Up on the foils, the hulls top out at around 30 knots, and the 25-knot cruise yields a 50-mile range. The interiors, created by BMW Designworks, include one cabin with a head and refrigerator (the Open), and another with deck-to-header glass windows and a sound system designed by Oscar- and Grammy-winning composer Hans Zimmer (the Icon) that works well as a superyacht tender. “The ride, the sensation of flying above the water in near silence, is part of the upscale experience,” says Tyde managing director Christoph Ballin. “You don’t miss the horsepower.”

The partnership is particularly satisfying for a guy who couldn’t give away an electric jet ski 15 years ago. Back then, Ballin met the 2008 world champion paddleboater, who produced about 0.5 horsepower with his legs, but propelled his paddleboat to 16 knots.

The trick? Foils. Fascinated by the idea, Ballin hired the paddleboater to develop a foiling PWC. The prototype hit 18 knots using a 4 hp motor. At the time, Ballin had founded Torqeedo, a maker of electric marine motors, but he had no interest in becoming a PWC builder. Instead, he offered the design to every builder he knew, free. No one wanted it.

In 2021, BMW reached out. The company’s battery pack had become commonly used by other builders (it even resides in the Frauscher-Porsche project), and it, too, wanted to show what it could do in marine. Ballin pitched the team on the benefits of foiling, especially for an electric boat, and Tyde was launched.

“Foiling has made a lot of progress since the 2013 America’s Cup, where it made its debut,” Ballin says. “Before, the knowledge only existed in the heads of a few engineers, but it’s gone from an art to a science.” Today, there are a handful of companies that design what he calls a “proper flight system,” most notably Candela, which has been producing foiling electric boats in Sweden for five years, and San Francisco-based Navier, which has a 30-foot foiling powerboat called the N30.

Drivetrain developments also played a role in the progression of electric boats. The energy density of battery packs hasn’t changed much in recent years, so a lot of the gains have come from coaxing more efficiency from the power chain. That includes, shafts, drives, sensors, connectors, and the cooling system.

Polish startup Siala has introduced 45- and 59-footers with hulls designed to match its electric propulsion. For 15 years, Siala founder Stanislav Szadkowski had a controlling interest in ICPT, Europe’s largest battery-system maker for commercial electric vehicles, so he understands the importance of assembling the right components.

Instead of cobbling together a Frankenboat, the team designed a fast, sleek weekend cruiser that will compete with non-electric vessels from Pardo, Vandutch and Wajer. Besides range-efficiency and speed, Siala’s proprietary battery system includes a safety management system (SMS) for optimal performance, which includes an automatic failsafe that limits output if the driver puts too much pressure on the batteries.

“Performance is a function of managing the thermal load,” adds Mitch Lee, CEO of Arc, which is based in Los Angeles. “You need to eject the heat to maximize the system.” Lee’s ARC One does that via a software-controlled module that allows the 24-foot towboat to produce a combustion-like 525 horsepower and hit speeds of 40 mph. It can run for four to six hours at slower speeds, he says. That model has already gone out of production, but a new design, the Arc Sport, will offer similar speed and range, with the ability to offer wake surfing.

Arc achieves that performance by building many of its systems in house, supplemented by parts developed in the auto industry, and by building the boat around the drivetrain. “Electric cars took off when they started designing around the battery pack,” he says. “That’s happening now with boats.”

No surprise that Lee’s partner, Ryan Cook, previously worked as an engineer at SpaceX, a corporate cousin of Tesla. Their team includes refugees from Elon Musk’s car company as well as Rivian and Lyft.

Another former Musk employee, John Vo, served as Tesla’s global head of manufacturing for six years before eventually founding Blue Innovations Group (BIG). His Florida company has taken a similar approach with its 30R, starting from the keel up with custom systems and a production method modeled on the car industry. The resulting 30-foot cruiser offers a projected top speed of 45 mph and a 100-mile range at 20 mph. The boat’s foldout transom places it head-to-head with non-electric weekenders from Europe and the U.S.

Like the Arc, the BIG has an aluminum hull, telemetry (remote updating of systems by the factory), an integrated control module and solar panels built into a hard top that help run systems.

Large solar-panel arrays are integral to recharging banks of batteries on vessels like the Silent 62 three-deck power catamaran, one of the largest electric yachts on the water. The panels are designed across the top for maximum exposure to the sun. The catamaran design is also more efficient than a monohull, which has a lot more wetted surface, while giving owners much more interior volume, thanks to the large beam.

The Silent range has become much more stylish since the company first started building boats a decade ago. The cats then were purely functional, boxy and uninspired. Designers are now seeing opportunities for dressing up the interiors, while making the exteriors as sleek as the form allows.

Most builders of larger cruisers, say in the 50- to 80-foot range, install hybrid diesel-electric propulsion because their owners don’t relish running out of juice miles offshore, with no power source other than the sun. The diesel part of the equation also increases the vessel’s speed, range and weight-carrying capacity.

Cosmopolitan Yachts incorporates solar panels across the top deck of its 70-foot power cat, which feed its banks of lithium batteries. But the Spanish builder also has two diesel generators for alternative power. The shipyard could have reduced overall weight by cutting amenities, as full electric boats must do, but the hybrid power allowed it to go full luxury.

The standard layout includes six en-suite staterooms, crew quarters, a hot tub on the top deck, a wet bar, a full galley, desalinators and ice makers. There’s also a tender/toy garage and foldout swim platform. In other words, all the amenities of its fully diesel-powered competitors but with far fewer carbon emissions.

Cosmopolitan’s Ivan Salas Jefferson says his company has taken full advantage of the progression in electrical propulsion and solar panels, as well as the materials. “We could have built this boat five years ago but probably would not achieved the same standards,” he says.

Fully electric power for megayachts remains years away, according to Stefano de Vivo, chief operations officer of Italy’s Ferretti Group, who oversees superyacht brands like Custom Line and CRN. “The batteries are very heavy, making them a challenge for larger yachts,” he says, “so we began studying the possibility of electrifying one of our smaller boats, the 27-foot Riva Iseo.”

Riva launched the production electric version called the El-Iseo in January, with a Parker Hannifin motor and a battery-pack supplied by Podium Advanced Technologies, an auto tech company.

“It would be easy to make an electric boat with 100 miles range, and in bigger sizes, if you do not want the same level of comfort and luxury that a normal Riva has,” de Vivo says. To split the difference, Riva dumped non-essential components that added weight, such as the mahogany transom, but kept everything else the same, winding up with a top speed of 40 knots with a 25-mile range and a cruising speed of 25 knots.

In search of even better performance, the builder is now considering a larger boat with foils, showing that even a traditionally minded company like Ferretti can keep up with changing technology as long as one thing remains true: The boat needs to have the same amenities and build quality, and performance must be close to its non-electric counterparts.

Of course, there are other measurable benefits. “It still has the same sense of richness about it,” says de Vivo of the El-Iseo. “But now it’s much quieter.”