How Fashion Houses and Jewellers Are Giving Swiss Watchmakers a Run for Their Money

Perched on a couch last April in a private room inside Chanel’s sprawling space at Watches & Wonders, Frédéric Grangié and Arnaud Chastaingt appear positively serene. Outside, the world’s largest watch fair buzzes with energy as press, retailers, and VIP clients gather for a first-hand glimpse of the latest from a wide swath of brands, including the industry’s biggest hitters. Unlike at Paris Fashion Week, where Chanel is perpetually one of the hottest invites in town, here in Switzerland the maison’s iconic logo might actually be a disadvantage. The fashion house must vie for attention with horological heavyweights such as Patek Philippe, which dominate the landscape and have catalogs of coveted models dating back hundreds of years. But Grangié, Chanel’s president of watches and fine jewellery, and Chastaingt, director of its Watchmaking Creation Studio, are unfazed. They insist that Chanel’s fresh perspective, combined with an incomparable fashion history and laser focus on savoir faire, actually gives the house an advantage in the world of haute horology.

“When we look at competition—and we are very respectful of them—some of the houses have been there for two centuries, some claim even more, but we are still in that phase where everything that we are creating is actually part of a living patrimony,” Grangié says. “We see the difference in what we are presenting because, of course. The biggest mistake that we could have made is to be a fashion company making watches, as opposed to a watchmaker whose manufacture and craftsmanship is at the service of creation.”

Chanel didn’t enter the watch domain until 1987, but in the short time since, it has become a trailblazer in terms of both innovation and creativity. Its J12 X-Ray, which debuted in 2020, was the first timepiece to feature a case and bracelet made from clear sapphire crystal; typically used to cover watch dials, the material is so hard it can only be machined with diamond-tipped tools. It’s also extremely expensive and difficult for companies to produce. Cutting-edge watch brands such as Hublot, Richard Mille, and Bell & Ross (in which Chanel has a minority stake) had produced the material for some of their special high-end cases, but the J12 marked the first time a sapphire-crystal bracelet had appeared on the market. “We had a competitor, a very important one, come to us here, and when they saw it they said, ‘We tried to do it and it was a nightmare,’” Grangié recalls, chuckling and adding, “I can confirm it is a nightmare.” Nevertheless, Chanel followed up this year with a version in pink sapphire crystal, even more difficult thanks to the formidable challenge of maintaining colour consistency across the limited edition of 12. It’s just one example of how Chanel—alongside other fashion and jewellery houses from Bulgari and Van Cleef & Arpels to Hermès and Louis Vuitton—is elevating its watchmaking game, giving brands with centuries-old horological history a run for their money in the process.

Watches used to be an afterthought for luxury brands looking to expand their lifestyle portfolios. At jewellery houses, timepieces offered male clients a reason to treat themselves while buying baubles for their significant others, or they were seen as a mass-marketing tool, a means of enticing clients who might not be able to afford a million-dollar high-jewellery necklace or five-figure handbag. But as social media began luring an entire new generation of watch enthusiasts—a trend that accelerated hugely during the pandemic—luxury houses began taking the category more seriously, seeing the long-term potential of upping the ante on both design and technical movements and increasing their investments accordingly. The result has been some of the most creative and challenging watchmaking happening anywhere in Switzerland—even if collectors have been slow to recognize it.

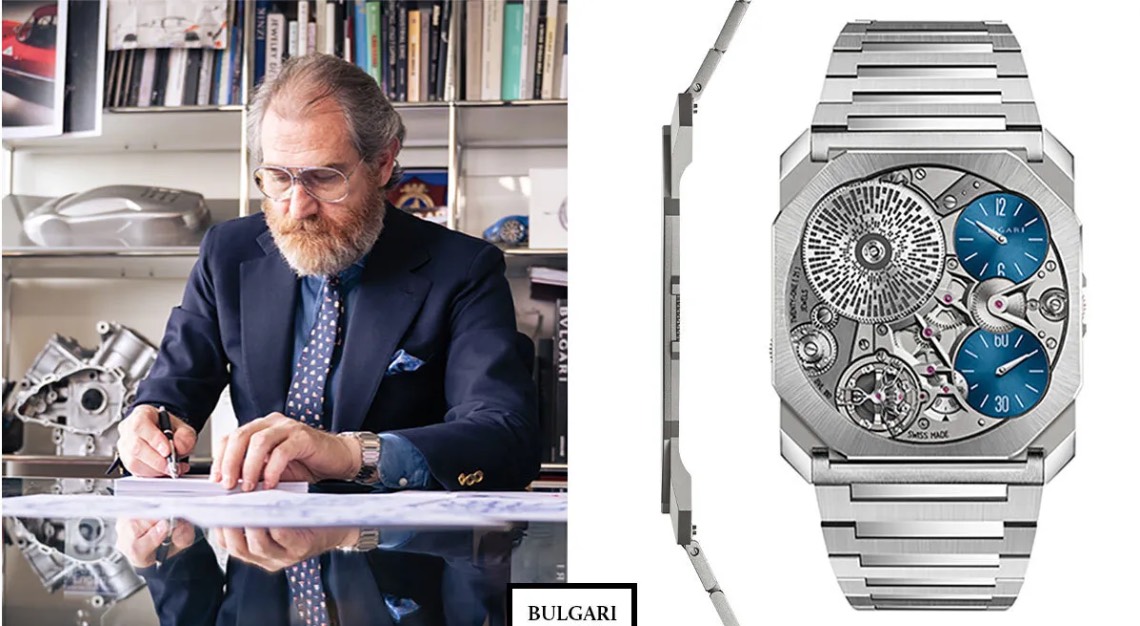

The race to compete for headline-grabbing horological feats has become fierce, and some of the creations defy belief. Take the ongoing tug-of-war between two houses with jewellery roots, Bulgari and Piaget, over laying claim to the most complicated timepieces in the thinnest possible cases. Piaget took ultrathin engineering to a new level in 2018 when it created the Altiplano Ultimate Concept, the thinnest mechanical watch in the world at the time, measuring an incredible 2 mm thick; the previous record holder, the Master Ultra Thin Squelette from longtime traditional watchmaker Jaeger-LeCoultre, suddenly seemed hefty at 3.6 mm. Just four years later, Bulgari one-upped Piaget with its Octo Finissimo Ultra, which slimmed down to a mere 1.8 mm thick—a literal hair thicker than a quarter, despite packing 170 components and 50 hours of power reserve. It marked Bulgari’s eighth world record for thinness in the Octo Finissimo line. Some consider it a gimmick, but the race to reduce gave the company bragging rights over elite watchmakers in an industry where it’s hard to stand out.

“I remember very well when I said, ‘Why does a client today have to buy a Bulgari watch?’ ” says the company’s product creation executive director, Fabrizio Buonamassa Stigliani, recalling the early days when the Octo Finissimo was just an idea. “We are not linked with any path. We don’t follow the sport model. We are not in golf or in polo. We are not in aviation,” he notes. The label did have the Bulgari Bulgari timepiece, a successful branded fashion watch from the ’70s that was revived this year, but he says he began challenging the executive team to green-light more complicated pieces. No one had expected them to be able to create a movement at that level, and yet “we have this manufacture inside, and we are able to create the most ultrathin watches,” so why not use it to their advantage? “We started to use the story of [setting] the record to switch the lights on [in] the watches business,” Buonamassa Stigliani says.

The drive to bring something exciting and original to market is fueling a rush of new ideas, many from overlooked sources. Van Cleef & Arpels, for instance, infuses its 118 years of jewellery expertise into wildly complicated automaton wristwatches and clocks behind intricate facades. Unlike many traditional watchmaking houses, Van Cleef often leads with design and storytelling, with technical development serving as the means to turn its fanciful imaginings into reality.

The company has been creating complex automaton timepieces since 2006; its most recent example, Brise d’Été, boasts a field of grass and violets that appear to waft gently in the wind. A pair of butterflies crossing above indicate time on a retrograde time scale. “What’s interesting there for us—besides the idea of the poetry of time, which is why we call these watches Poetic Complications—is that when we started to work on these projects, we found out that they were technically very, very complex,” says Nicolas Bos, the former global president and CEO of Van Cleef & Arpels who is now the CEO of its parent company, Richemont. Van Cleef spent seven years developing table clocks that presented the same concepts on a much grander scale. The first example, Automate Fée Ondine, came to life in a whimsical scene set with a jeweled fairy resting atop a lily pad. “It required the expertise and inventiveness of around 20 workshops in France and Switzerland to devise this extraordinary objet,” says Bos.

Masterminding creations at this level also requires in-house wizards, and many brands have strengthened their teams in order to construct even more advanced timepieces. When Van Cleef & Arpels director of research and development Rainer Bernard joined the company from Piaget in 2011, he was one of just four people hired to accelerate the watchmaking vision. Now, team headcount is at 20. Bernard says the fantastical ideas dreamed up by the house foster new mechanical achievements. “It actually gets us to places, technical places, where nobody has been,” he says. “This is why, for a while, we created between three to five patents every year.” These achievements are not for bragging rights on technicality but rather milestones leading to the creation of museum-worthy pieces. Take for instance the brand’s magnum-opus table clock, the Planétarium—a wonderland of rotating jeweled planets in a piece measuring nearly 20 inches high by 26 inches in diameter—where each sphere moves at its genuine speed of rotation set to a melody created with Michel Tirabosco, a Swiss musician and concert artist. It reportedly had a price tag of almost US$10 million. “Since I’ve been here, with all the elements we put into place, we have more tools and more possibilities to really create and be crazy about our stories,” Bernard says. “So, we can do things we only dreamed of a couple of years ago.”

The competition to wow collectors has become so stiff that, for some, hiring internally no longer suffices. Instead, luxury labels are snapping up revered Swiss manufactures whole or investing in smaller independent brands with elite expertise. Bulgari was an early pioneer of the practice, purchasing Gérald Genta and Daniel Roth in 2000. Buonamassa Stigliani joined the company just a few months later and says the acquisitions were key to Bulgari’s watchmaking growth. “It’s true that we found an amazing savoir faire, but it’s also true that we spent a huge, huge effort to achieve these results, because the idea was to have new movements,” he says. “The idea was to buy high-horology manufactures to find our path and to be the owner of our destiny.”

Having to source movements from outside manufactures poses several problems, including a lack of exclusivity and the potential for supply delays. But most importantly, bragging rights are typically reserved for companies that create their own. In-house production is a play for a rarefied, well-versed clientele. “You have to use a different language,” Buonamassa Stigliani says of appealing to serious connoisseurs. “You have to talk about the movement. You have to talk about technical constraints. The collector doesn’t talk with you if you’re talking just about shapes.”

Chanel has followed a similar path, making acquisitions that are both prestigious and technically adept. In 1993 it purchased G&F Châtelain, known for producing high-quality cases and movements, and in 2019 it acquired a minority interest in Swiss movement manufacturer Kenissi, an important supplier of sapphire-crystal glass to the industry. Chanel also owns stakes in Bell & Ross, Romain Gauthier—which helped Chanel develop its first complication, a jumping hour, in the Monsieur watch from 2016—and F. P. Journe. In August of this year, the Parisian house announced a surprise investment in avant-garde darling MB&F.

“Obviously, we are making our own watches, but we are also a supplier to many, many other houses, and that’s always been very Chanel,” says Grangié. “It’s the same thing with couture. The house owns many, many métiers—more than 35 at this point. We work for all the great names.”

Of course, it wouldn’t be a luxury showdown without LVMH at the table. In 2011, the conglomerate purchased La Fabrique du Temps, a manufacture founded by watchmakers Enrico Barbasini and Michel Navas, who cut their teeth making ultra-high-end movements for Patek Philippe, among others. Based in Meyrin, Switzerland, the atelier is staffed with designers, engineers, and craftsmen who create timepieces for Louis Vuitton, Gérald Genta, and Daniel Roth. It has enabled Louis Vuitton to make some of its wildest and most inventive watches, such as the recent Tambour Opera Automata—a US$580,000 automaton watch, nominated for a Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève prize—that pays tribute to the Sichuan Opera’s Bian Lian tradition with a retrograde-minutes and jumping-hours function. Such over-the-top pieces aren’t for wallflowers, or even the typical watch enthusiast, but there’s no denying the sophistication of their calibers.

Meanwhile, Jean Arnault, the 26-year-old son of LVMH honcho Bernard, has been hard at work overseeing the creation of beautifully crafted, if slightly more practical timepieces for Louis Vuitton, where he is the director of watches. Drew Coblitz, a Philadelphia-based alternative-asset-fund manager and seasoned watch collector, says he was interested in the Tambour Automatic when it came out, but talking to Arnault was what convinced him to purchase the timepiece. “You just get the impression that he’s supersmart and detail-oriented and thoughtful product-design-wise—the whole nine yards,” Coblitz says. “And the thing that he’s trying to do, branding-wise, is just really hard. It’s got to be one of the hardest things to do in watchmaking.”

He’s referring to the attempt to shift perception of Louis Vuitton from a fashion house to a maker of bona fide collector watches—and, with prices running from roughly US$23,000 to US$200,000, clients should expect the kind of top-notch watchmaking the house is delivering. While some of the high- horology pieces are for a flashier clientele, the Tambour and Escale lines are attracting collectors who, like Coblitz, care about finesse and nuance but want a more traditional look. “The amount of little-detail nerd stuff in the Tambour is killer,” Coblitz says. “And that’s before you turn it around, because the movement finishing is very nice.”

Creating this level of finishing on a series-production piece versus a limited edition such as the Tambour Opera Automata, though, is a stretch on resources, which means luxury houses are sizing up more manufactures to add to their rosters. Like Louis Vuitton, Hermès is not content to remain on the sidelines. This year, for example, it debuted the Arceau Duc Attelé, a feat of mechanical engineering that combines a triple-axis tourbillon with a minute repeater—the crème de la crème of complications—with hammers charmingly crafted as horse heads. The latest industry buzz circulating around longtime rivals Vuitton and Hermès, both famed predominantly for their premium leather goods and handbags, is their rumoured competition to buy Vaucher, an elite Swiss manufacture known for its high-quality watch movements and components.

This summer, it was announced that niche watchmaker Parmigiani Fleurier and its network of subsidiary suppliers of watch parts, including Vaucher, are collectively up for sale by their parent company, the Sandoz Family Foundation. Hermès, which has owned a 25 per cent stake in Vaucher since 2006, may seem like the logical suitor. But the house is now reportedly vying with LVMH for full ownership of the manufacture, which also supplies parts to other high-end watchmakers, including Chopard and Richard Mille; LVMH-owned TAG Heuer also outsources its higher-end movements through Vaucher. Hermès, Vuitton, and Parmigiani declined to comment for this article, but whoever gains control of the prized facility will have leverage over many of its competitors, and could even become their primary supplier.

As luxury brands continue to develop their watchmaking prowess by absorbing and investing in smaller specialized businesses, they pose a potentially significant challenge to the industry. Chanel, for its part, sees the business strategy as an opportunity to push boundaries. “Your competitors, who are also clients, will push you to develop things that you will not do for yourself,” says Grangié. “Then you become better at what you do, and you manage to have a model that will make your business sustainable over the long term, because you have those clients as well. To us, it’s a win-win proposition.” But for more-established watchmaking houses, the creativity inherent to fashion- and jewellery-first houses, backed by Switzerland’s finest horological specialists, could present a major threat.

Some are wise enough to move beyond their comfort zones: Just last month, Patek Philippe launched its first new collection in 25 years, aimed at a younger clientele. But Chanel, for one, is already barreling full steam ahead. “Next year, you will see something extraordinary that took a long time in the making,” hints Grangié. “We are creating an ecosystem to support our business and our future ambitions that relies on either the highest level of expertise or incredible names that we have become associated with first.” With historic houses seeking to attract fresh attention just as the fashion-forward upstarts hit their stride with never-before-seen innovations, we just might be on the brink of a remarkable new era in luxury watchmaking.

Previously published on Robb Report USA.

Photography: Hermès, Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Van Cleef & Arpels, Bulgari

Featured photo by Clement Rousset/Van Cleef & Arpels