Selberan’s latest release Eva, is a collection of earrings, necklaces and rings riff on the circle – a shape which has come to represent eternity, femininity and wholeness. The collection is realised with diamonds, sapphires, rubies and pearls combined with 18k white and yellow gold, and offers plenty of versatility in stacking and transformation, transitioning elegant day looks into glamorous evening regalia.

It is perhaps fitting that this collection was one which has also come through its own cycle in its creation, relying on the mastery of gemmologists, designers, goldsmiths, masterpiece makers, stone setters and polishers within Selberan. What is perhaps more compelling is that most of the artisans behind its creation are Malaysians born and bred, a legacy borne from serendipity.

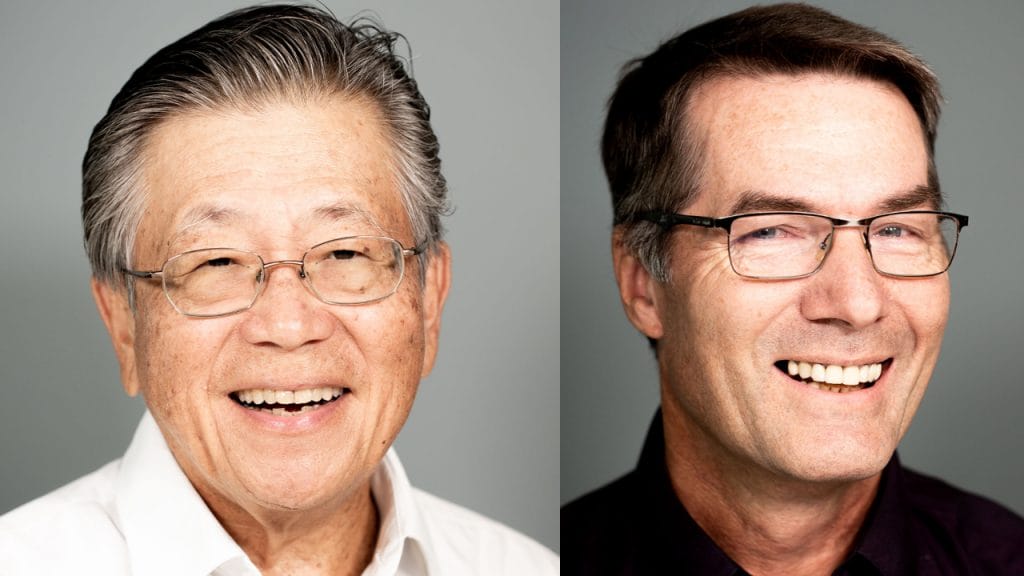

Tan Sri Yong Poh Kon, Royal Selangor International’s chairman remembers how his path crossed with Swiss jeweller Werner Eberhard and Austrian gem-setter Walter Anglemar in the early 70s. At the time, the pair were based in Perth, Australia and producing fine European jewellery which were being sold by their wives to a select clientele of Australians, Malaysians, Singaporeans and Thais.

Their difficulty in obtaining skilled labour in Australia, coupled with the distance from Perth to the main markets which they served, led them to the doorstep of Royal Selangor, and to Yong himself – the third-generation descendent helming his family’s pewter company. Even as he was continuing the expansion of the family business – today the world’s largest pewter producer with stores from Sydney to London to Toronto – Yong recognised the exceptional elegance in the duo’s jewellery.

“At the time, jewellery in much of Asia was bought from goldsmiths for their gold value alone,” he remembers. “It was measured as 22k (91.6 percent) or 24k (99.9 percent) – gold for gold’s sake.” What he saw in the creations by Eberhard and Anglemar was an element of design and fine features which were very much in vogue on the European continent.

The critical point in classical European jewellery’s conception is the usage of 18k (75 percent) gold, with a combination of copper, palladium or other precious metals resulting in a stronger alloy and hence, sturdier claws in which gems could be set within. “This way, it’s not easy to knock the gem out of its setting and you don’t just lose a diamond.”

Their mutual admiration for each other’s craft and the comparative advantages of Malaysia, with its English-speaking population and lower labour cost compared with Singapore, resulted in the 1973 founding of Selberan – a portmanteau of Selangor, Eberhard and Anglemar. “We offered an additional incentive, which was to provide 20 or so craftsmen who have had at least a three-year tenure with us from a pool of hundreds,” Yong recalls. This identification of the right talent, who also exhibited the right temperament for craftsmanship, set Selberan on an impressive trajectory. From its maiden shop at Yow Chuan Plaza – known today as The Intermark – Selberan found its way to export markets in Europe courtesy of the wives’ long-standing selling links, including the window cases of Switzerland’s famed Bucherer watch and jewellery emporium, a bastion of European luxury along Zurich’s Banhofstrasse – its main commercial thoroughfare.

The brand also blazed a trail in its home market of Malaysia, insisting first and foremost on quality, and clients were soon converted to understanding the intricacies of fine jewellery, such as the 4Cs in diamonds. “The appreciation in diamond grading was virtually non-existent then,” Yong recalls. By imparting this knowledge, Selberan helped its clients understand that its diamonds always conformed to the ideal cut of 57 facets, proven to generate the optimal amount of brilliance with total internal refraction. “We offered only truly to nearly colourless diamonds, D,E,F, G, H and maybe I – we told clients not to worry about what comes after.”

This jewellery buying public became multi-generational supporters, going to Selberan for engagement rings, anniversary gifts and coming-of-age pieces for their children. For Yong, the most gratifying aspect has been in proving that the transfer of skills was possible, with the reality of fine European-styled jewellery now produced in the heart of Kuala Lumpur with early hits such as its Archive Ring in its year of founding. “When we set up the venture, we told our partners that this endeavour was not from scratch – we had talented prospects who could learn their repertoire,” he recounts. “And, within a generation – the skill had permeated among the ranks of our craftsmen and they could produce at a level similar to what took the European jewellery maisons centuries to hone.”

Around the same time as Selberan’s founding, an 18-year-old Gerd Joachim Neumann was looking for a field in which he could enter after graduation. In his city of Pforzheim – known as the Golden City for its jewellery and watch-making industry – almost 90 percent of the population, and every family, was involved in the jewellery industry. “I liked handcraft work so I went in to learn drawing, smithing and engraving,” he says, adding, “and just like that I caught fire.”

Today, Neumann has served as the master craftman at Selberan for the past seven years, bringing a wealth of experience. His 46 years in jewellery making means that he has had the time to master the various disciplines associated to jewellery making. He compares the craft to what experts say about being able to master piano, that you need a minimum of 10,000 hours of training – or approximately 10 years – to be able to master one specific skill. “I was fortunate that in my work I was able to learn the various processes and am now committed to up-skilling the artisans in our manufacture to also appreciate the various stages of jewellery making.”

This well-rounded training means that Selberan’s technical staff are able to realise the designers’ masterpieces, with strong input of their own. “For Selberan, this base of understanding helps us to build solutions which enhance the overall result,” he says. Neumann references the Eva round pendant which features a kind of ‘roof design’. To enable this curvature, his team had to work a slight tension into the circle, which was eventually achieved through a meeting of minds between design and technical teams.

The Selberan pieces today exhibit both the quality first ethos of its founding, with a reliance on ideal-cut diamonds and noble metals. This is combined with a deep learned expertise and contemporary design vision. “I learnt from my mother on how to discern the beauty in things,” Neumann states. “Developing nice, elegant jewellery is a lot like understanding nature – you have to see how designs have a correlation to nature, and know the difference between what is natural and what is clumsy.”

Adhering to what Neumann calls a particularly narrow line has helped Selberan to also gain the attentions of clients such as the World Gold Council and various other governmental bodies and corporations. Its private commissions include a transformable diamond tiara of 624 ideal-cut diamonds which can be dissembled into a pair of earrings, a bracelet, necklace and kerongsang (brooch). In 2018, Coca-Cola commissioned a trio of its classic cans done in solid 22k gold. Neumann remembers the task as being particularly challenging, as they had to figure how to keep the walls 0.2mm thick and match the bottom and top exactly. “We also had to place the tab ring last because we needed to let the heat out from within.”

Now in its 47th year, Selberan’s long links helps it come ahead of the others when it comes to sourcing for the best conflict-free diamonds, and finding matching gems and semi-precious stones. This “grown relationship” as Yong describes, means that Selberan is able to “make any type of jewellery that its client desires.” Even a can of Coke in 22k solid gold.