Big Names In Horology Are Creating Highly Complicated Yet Easy-To-Wear Watches

For a brand that is seen as one of the more traditional of watchmakers, Patek Philippe still manages to shake things up admirably. Take this past spring and summer. After industry “pundits” confidently predicted that Patek would not be launching anything new this year, the company dropped a limited-edition steel time-and-date watch to celebrate the opening of its new manufacturing building. Then, just before he took his summer break, president Thierry Stern emailed his clients to let them know he was unveiling three more watches, each with a superlative complication: a minute repeater, a split-seconds chronograph, a new version of the perpetual-calendar chrono 5270. And not a Nautilus among them.

The last five years or so have been characterised by a mania for steel sports watches, and over that time prices for Patek’s Nautilus and Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak have completely ignored the forces of gravity—had Isaac Newton been working today, he would not have come up with his career-defining theory looking at prices of these two classic 1970s integrated case-and-bracelet designs by Gérald Genta. Following this ineluctable rise, steel sports watches have appeared all over the place, even at niche makers. Czapek’s handsome Antarctique and Moser’s pleasing Streamliner are just two of the more recent passengers to board the luxury steel-watch bandwagon.

Whether Patek was trying to send a message with its trio of unexpected complications is not known, but what is certain is that horological Kremlinologists will be looking for one, the most obvious being that complicated watchmaking is once again taking center stage and beginning a new chapter in a story that originated almost two centuries ago.

Abraham-Louis Breguet, the Mozart of the personal portable timepiece, composed the overture for the first act of the grand-complications drama during the 1780s, when he embarked on what was then the most complex multifunction timepiece. It was not completed until 1827, four years after his death. The watch, known as the Marie-Antoinette, has since become one of the most famous works of human creativity, not least because it was once stolen in a spectacular theft and not recovered for decades.

As the 19th century progressed, a complicated pocket watch became the must-have tech gadget for the super-rich and a sine qua non of the great World’s Fairs, which were a cultural phenomenon of the times. The Paris exhibition of 1878 saw the debut of Leroy’s 11-function timepiece, which inspired a Portuguese collector to commission the fabled Leroy 1, the winner of the Grand Prix at the Paris exhibition of 1900 and the possessor of around two dozen complications (the exact number depends on whether you count such non-horological functions as a barometer and altimeter).

The ingenuity arms race intensified during the early 20th century. Auto tycoon James Ward Packard ordered 13 important watches from Patek Philippe, culminating with a 10-complication extravaganza that included a celestial map of the night sky above Packard’s hometown of Warren, Ohio, with 500 stars of varying size picked out in gold.

New partners at J. P. Morgan’s bank could expect to be presented with a handsome Frodsham open-face tourbillon with minute repeater and split-second chronograph. Between 1897 and 1931 (after Morgan’s death in 1913, his son perpetuated the custom), 25 such “Morgan-caliber” watches were presented.

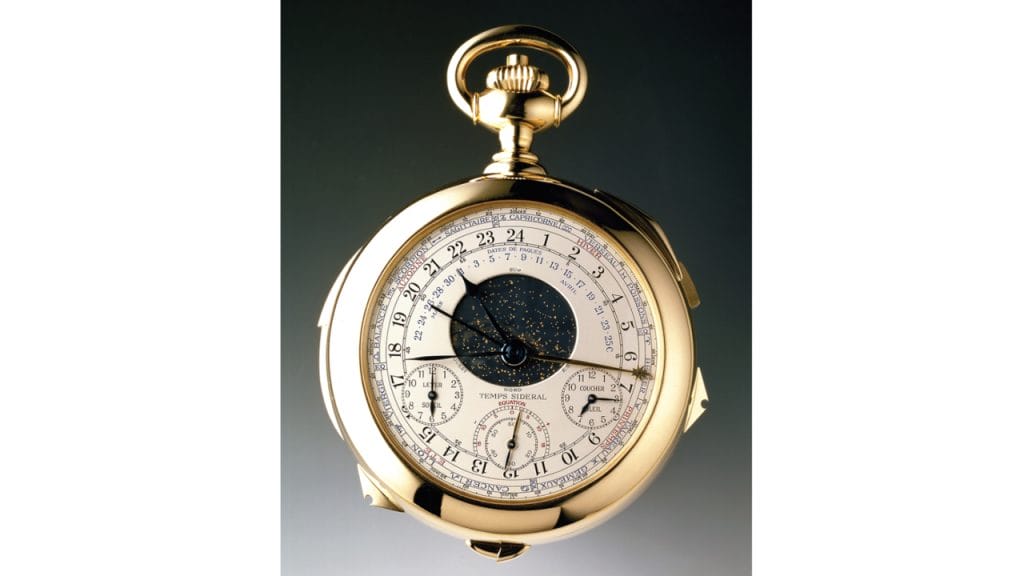

Egypt’s kings Fuad and Farouk exhibited a fondness for high complications from Vacheron Constantin. Another Vacheron lover was Henry Graves. The archives of the 265-year-old Geneva firm contain several letters from Graves, a New York banker who would by now have been obscured by the swirling mists of history had he not bought the grandest of all grandes complications, this one by Patek Philippe. Known simply as “the Graves,” it was completed in 1932 and featured two dozen complications; it fetched more than US$24 million (about RM99 million) when it sold at auction in 2014.

The Great Depression, the popularity of the wristwatch, World War II and the advent of the battery-powered quartz-regulated watch seemed to consign the complicated mechanical watch to the history books and the dustier corners of museums. But in 1989, Patek Philippe celebrated its 150th anniversary with the Calibre 89, a monumental timepiece with an unprecedented 33 complications, including, my favourite, one that predicted the date of Easter.

Only a handful of these behemoth pocket watches, for which you needed pockets that were both metaphorically and physically deep, were ever made, but their cultural significance, as the curtain raiser on the second act of the drama, was immense.

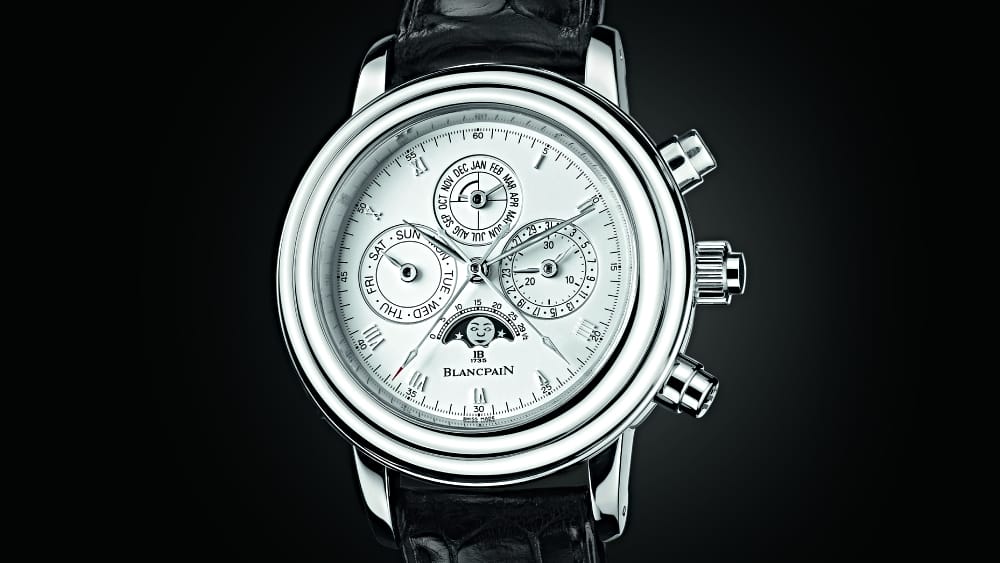

During the late 1980s mechanical watchmaking was only just out of intensive care after a decade-long battering by cheap, accurate electronic timepieces, but a few visionaries had realised that if they were to make complicated mechanical models, this time primarily for the wrist, they would find a market. I still remember the excitement that surrounded the appearance of the IWC Grande Complication in 1990, only for it to be eclipsed three years later by the IWC Destriero Scafusia. At roughly the same time, Audemars Piguet launched the Jules Audemars Grande Complication and Blancpain its 1735.

The grand complication was back, and by the early 21st century elaborate watches were no longer the rarities they had once been. Feats of engineering and craftsmanship had instead become expected. Where once tourbillons had been objects of incomprehensible wonder (some would argue that a tourbillon, as it only assists in the accurate running of the watch rather than bestows an additional function, should not be counted a complication), they were now commonplace. Minute repeaters were heading the same way when the storm of the financial crisis hit, and extravagant oversize watches were suddenly eschewed in favour of more understated timepieces, either smaller, slimmer, elegant dress watches or go-anywhere steel sports pieces.

And it is out of these last two trends that a new appreciation of inventiveness is being forged as we enter an era in which complications have never been so wearable, in terms of both styling and durability.

Hugely intricate pocket watches such as the Calibre 89 or Vacheron Constantin’s 57260 are difficult to wear in the conventional sense. The Blancpain 1735 was such a refined and delicate instrument that I recall once hearing how an excited client put his 1735 on his wrist and did not take it off when jogging, meaning that, almost as soon as it was delivered, it was on its way back to the workshop.

Today a grand complication is no longer expected to be just a source of wonder but rather a daily pleasure. “The challenge is not to create one amazing, unique grand complication but to reproduce it to perfection and to be able to propose such rare, complex timepieces,” not only as bespoke one-offs but in the wider collection, explains Patek Philippe’s Stern. “The range of the offer is unique. We have all types of complications. But in my view it is Stern-family philosophy that differentiates us from others, makes a Patek Philippe grand complication special to collectors and those passionate about the brand. We are not only looking at the pure technical complexity. This is not enough. What I really care about is that, however complicated our timepieces are, they should always be aesthetically appealing, comfortable to wear, easy to use and at their best when worn on a wrist. I do not want to create these rare watches just to be kept in a safe.” His point would seem to have been proved last November, when a steel, 20-complication, reversible Patek Philippe Grandmaster Chime—which sounds the date as well as the time and is famous for being the first grande sonnerie and most complicated wristwatch to enter the collection when it appeared as a limited edition in 2014 to mark the brand’s 175th anniversary—became the most expensive watch ever sold at auction, fetching more than US$31 million or about RM128 million (over 10 times its pre-sale high estimate).

Patek is not the only storied Geneva house releasing complications this year. Vacheron Constantin captured collectors’ attention with Les Cabinotiers Astronomical Striking Grand Complication Ode to Music, a chiming supercomplication that features not one, not two but three gear trains, for sidereal, solar and civil time. Vacheron one-upped itself with the even more impressive Les Cabinotiers Grand Complication Split-Seconds Chronograph Tempo, with 1,163 components and 24 complications, all housed in a reversible, wearable wristwatch.

Less showstopping but just as significant was the launch last year of its Traditionnelle Twin Beat Perpetual Calendar, which offers a two-speed caliber that extends power reserve to over two months, avoiding the need to reset the watch after long periods off the wrist: Put it in the safe, go on an extended holiday, come back, pick it up and put it on—the essence of fuss-free wearability. According to Vacheron’s Christian Selmoni, that is key to new-gen complications. “It is really a landmark application of horological ingenuity, a totally new way to think about managing the power-reserve autonomy,” he says. “It is part of a contemporary trend because I think that we want to be able to wear such a watch every day. We want it to be robust so that we can wear it on any occasion, and we also want a complication. This is something which is quite new. This is why I think we see so many developments in high complications that are housed in steel cases.”

Increasingly, a new generation of high-flying watchmakers are using new ideas and new technology to leave their mark on horological history with innovative and original ways of realising and re-envisaging complications.

“Demand for complications has been steadily increasing,” says Michael Fried- man, who runs the complications division of Audemars Piguet. “In the last five years we had the Concept Laptimer Schumacher, which was an entirely new approach to chronographs, where we essentially reverse-engineered a digital lap timer—which you will see on any iPhone—into a triple-column-wheel chronograph, which was unprecedented in the industry. We then worked on Supersonnerie technology,” to create the sort of minute repeater that is audible across a room, “which is now continuing to evolve. Most recently, we have been rethinking the perpetual calendar.” For its prize-winning ultra-slim perpetual calendar, a revolutionary redesign of movement architecture and the multifunctional nature of components meant that all parts could be on one plane, rather than piled atop each other.

“All three of those developments simply would have been impossible before the advent of computers and the relevance of technicians and engineers in the process of modern watch production,” Friedman says. “Perpetual calendars are hundreds of years old, but only now were we able to bring all layers down to one and essentially change the entire approach to how the perpetual calendar is produced. That was a combination of the traditional mindset and relying on advanced technologies.” And there’s more: A new tourbillon chronograph debuted in September, and a new Supersonnerie emerged last month.

The combination of traditional and unconventional approaches is also evinced at L.U.C, the haute horlogerie division of Chopard. Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, co-president of Chopard, is particularly proud of an award-winning minute repeater in which the gong and the crystal were made in a single piece. “They are supplied all in one piece and were not connected or milled,” he says. “That would have been impossible 20 years ago, but that is what makes it so interesting today. This is more than using a new material for the sake of saying we are using a new material. The technology has to be useful and bring new added value.”

In other words, the grand complication is no longer “just” a horological high-wire act; it has also improved the function inasmuch as joints that fix the gongs, whether screws or glue, can adversely affect the chime. While overcoming that flaw, L.U.C’s innovation makes the watch more wearable than ever.

“I’m glad we got to this idea of day-to-day use, that during tumultuous daily life you can have your minute repeater on, you can have your tourbillon on and you do not worry,” says Friedman, who sums up the appeal of the modern complication in one very simple maxim. “You just enjoy your watch and enjoy your life.”

As philosophies go, there are worse ones to live by.

Previously published on Robb Report.