At Gurney Paragon mall, located along the beachfront promenade of Penang’s famed Gurney Drive, one finds the Straits & Oriental Museum. This approximately 8,000 sq ft space is located on the uppermost floors of St. Jo’s – the heritage wing of Gurney Paragon – and comprises three distinct exhibition spaces dedicated to the efforts of its founder Ooi Wei Ming.

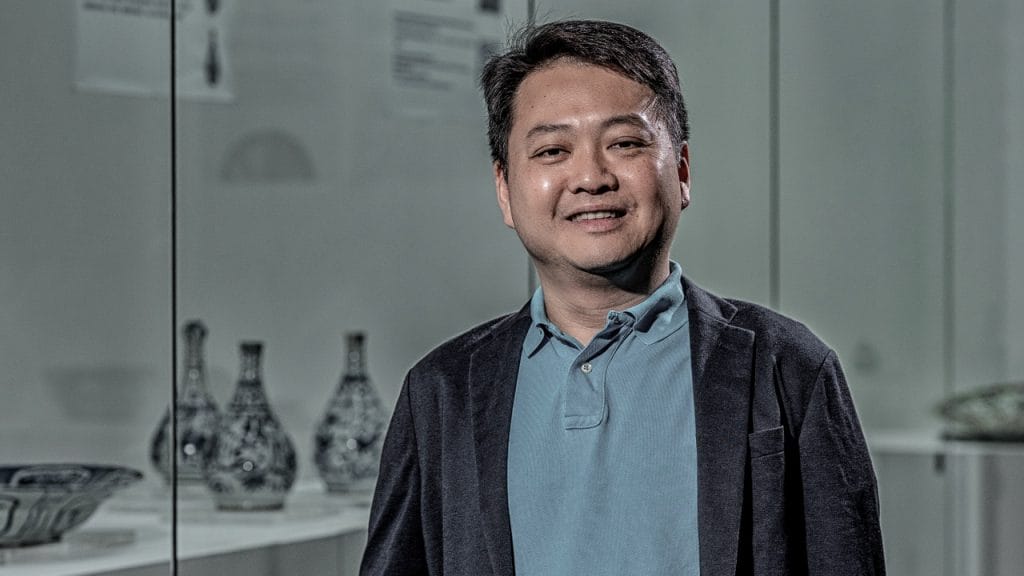

For the Penang-born and bred founder Ooi, a budding interest in predominantly Chinese porcelain eventually debuted as a full-fledged museum in September this year. The Straits & Oriental Museum is so named to reflect the story of China’s mastery of porcelain – which eventually influenced even Dutch pottery such as Delftware – as well as the story of Malaysia’s early years when the Straits of Malacca became the arterial waterway linking East and West.

Ooi recalls his earliest intimation with porcelain originating from an interest in imperial porcelain produced during the reign of the 18th-century Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty. “The pieces from this period showed the heights of Chinese pottery, and I began studying records, patterns and the history of porcelain at Christie’s and Sotheby’s where most of my collection is sourced,” Ooi says. Ooi adds that his purchases have been largely driven by the value of pieces which speak of the sense of heritage and belonging; be it that of the 5,000-year-old Chinese civilisation, or of artefacts which showcase the arrival and evolution of porcelain alongside the story of Malaysia.

In the first room of the Straits & Oriental Museum, visitors start with a an understanding of the evolution of ceramics which eventually became porcelain, as it attained a fineness and level of craftsmanship that made it prized across the world. Some of the earlier pieces relate to the Tang (618 – 906 A.D.) and Song dynasty (860 – 1279 A.D.) in which the ceramics were all produced for utilitarian purposes as is the case of a black-glazed tea bowl on display. “You can see that the ceramic then was a bit rough and not as well-defined,” says museum curator Alvin Chia who regularly hosts the walkthroughs.

By the time the Ming Dynasty rolled in (1368 – 1644 A.D.) the use of cobalt blue and white, known as ‘Qing Hua Ci’, showcased the intricacy of the finishing, with motifs such as the ‘Ruyi’ – a talisman of power and good fortune. In the room, Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911 A.D.) pieces highlight the use of iron ore to produce scarlet-coloured porcelain, with the presence of five-clawed dragons chasing pearls on some pieces denoting that it was produced for the exclusive use of the emperor.

Here, the exhibits also show the evolution of Chinese porcelain-making where artisans initially used a single firing to attach colours via the enamelling process, to multiple firings for multi-coloured ‘Famille Rose’ vases and bowls adorned with wisteria, lotus and bird motifs. A piece drawn from the collection of the Empress Dowager Qixi also showcases the use of gold plating to add adornment.

On another row, one finds a batch of green porcelain including a three-legged censer, which, as Chia points out, is difficult to produce as a result of the firing process which requires for all legs to be evenly made. These pieces of green porcelain segue into the second gallery dedicated to export ware, the pieces destined for overseas market.

In this space, the vast amount of international trade – half a millennia ago – is observed through the displays of green porcelain which got its export name of celadon, a European term used to describe the green ware from China.

In the same way, Kraak Porcelain obtained its name from carracks, Portugues ships which first transported the blue-and-white porcelain to Europe. Another range of porcelain on display here is 18th-century Canton ware, where the earlier famille rose pieces were also made for the export market (a marked difference lies in the gold plating that did not employ any cinnabar, an ingredient mainly used to ensure a longer-lasting application of the gold plating). “As it was meant for export, there was less quality control processes, it just had to look good.” Chia explains.

The displays wend into Straits Chinese porcelain – colloquially termed as ‘nyonya ware’, which showcases the belle epoque of the Peranakan age. Among them is a bowl decorated with phoenix motifs, to show that it was meant to be inherited by the eldest daughter of the family.

A third room within the Straits & Oriental Museum is dedicated to the salvaged pieces from shipwrecks, which are plentiful around the waters of both peninsular and east Malaysia. Among them are pieces made by the Chinese diaspora in Thailand who fled the motherland during the Mongol invasion. The ceramics clearly exhibit grooves and shapes that have been modified and made ornate to fit local customs and culture.

“This is the real Hai Di Lao,” Chia points out, referring to the act of deep-sea dredging which produced the shipwrecked exhibits. He notes that the museum balances the restoration of some pieces while maintaining others in the condition they are found, to show how the mineral pigment used in the paints had attracted sea life such as barnacles over time. In one corner, a nearly 1,000-year-old jar made of porous clay with a lid-locking mechanism shows one of the earlier means of refrigeration, as the jar was suspended to allow items within to stay cool while keeping flies and ants at bay.

In time to come, the exhibits will extend into the earlier dynasties such as the pre-Christian Zhou (circa 1050 – 246 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C – 220 A.D.) dynasties as well as the Tang dynasty (618 – 906 A.D.). “I’m now looking to collect especially the horse and clay figurines from these periods,” says Ooi of his growing collection.

Another aspect of his acquisition drive is to support the museum’s ‘Straits’ element, through the purchase of old coins, starting from the late 18th century, Straits Settlement notes, as well as documents such as stamps and debentures from nearly two centuries ago. “It’s really something to see the signatures of the early settlers in Penang during that time, purchasing parcels of land that we are so familiar with today.”

For visitors to the Straits & Oriental Museum, they will discover that the St. Jo’s annexe of Gurney Paragon is also populated by a separate gallery dedicated to contemporary art, a museum gift shop, the Wako Sushi omakase restaurant, a café and co-working space as well as the Straits restaurant and bar with a menu of Peranakan and local favourites.

“Of course I would love if this effort could grow into an establishment like The Met,” Ooi says of his vision for the Straits & Oriental Museum, adding, “for us now, we are happy to be able to transmit this cultural value to the visitors, to give them a sense of understanding of our shared past as we move into the future.”